Options and other derivative investments can feel like they belong to an insiders club of serious traders. And there’s a reason for that: Derivative products often involve leverage and risk. However, options can be used as part of a more traditional and even conservative investing strategy. You may also see options used in fixed index annuities, mutual funds, or other financial products.

In this article, we’ll go over some of the basics and review how we may use options at Bogart Wealth. (For ease, we’re including a glossary with some of the key terms we discuss at the end of this article.)

How Options Work

Think of your favorite New York Time’s bestseller. When a book becomes ultra-popular, we frequently see a movie or TV show adaption in subsequent years.

The book-to-movie pipeline is a perfect example of how options work.

When a book becomes popular, a Hollywood studio may buy the movie rights, giving them the option to turn that book into a movie for a certain period of time, as specified in their contract.

The result of this purchase can go a few different ways:

- If they don’t make the movie, the option they bought expires and they don’t recoup the money they spent on it.

- If they do make the movie, they could make a big profit.

- The book could get even more popular, leading other studios to try and buy the option for the movie at a higher price.

- On the other hand, readers could lose interest in the book. The first studio doesn’t want to make the movie. They might sell the option to another studio at a loss or simply let the option expire.

Options trading works in a similar way, but in this case, the underlying assets are securities like stocks and ETFs, not books.

What are Stock Options?

When you purchase an options contract, you’re purchasing the right (or option) to buy or sell a certain amount of stock, at a predetermined price, on or before a specific date.

A standard options contract gives you the right to buy or sell 100 shares, meaning options are leveraged. When a stock gains or loses $1, the options contract on that stock could change by $10. (That’s a purely hypothetical example-how options prices relate to the price of the underlying asset is complicated and not relevant here.)

The important takeaway is that options are leveraged and the price of the underlying asset affects the price of the options contract.

Put Options and Call Options

There are two types of options contracts: call options (the right to buy) and put options (the right to sell).

If you buy a call option, you’re generally betting that the underlying asset will increase in value-a bullish position. When you purchase a put option, it usually means you think the underlying asset may lose value-a bearish position.

Here’s where things can get a little more complicated. You can also sell options, meaning you’re taking the other side of the bet. Selling a call option tends to be mildly bearish and selling a put tends to be mildly bullish.

There are various ways to both buy or sell options contracts to enhance your investing strategy. For long-term investors, the two most common strategies include selling covered calls for income and buying puts as a hedge.

Covered Calls can Help Generate Income

When you sell a call option, you’re agreeing to sell 100 shares of a stock at a future date, for which you collect a premium.

A call is considered “covered” because the seller of the options contract owns 100 or more shares of the underlying. If the option is exercised (meaning at expiration, the buyer exercises his option to buy 100 shares at the specified price), you already own enough stock to cover that sale.

How Covered Calls Work

Generally, you sell covered calls at a price that’s higher than the current market price of the underlying stock or ETF. As long as the underlying asset closes below the contract price (or strike price) at expiration, you keep the premium. If the asset increases in value, you might be forced to sell your shares but it’s still a win: The underlying asset increased in value from the time you sold the contract and you keep the premium from the options contract.

At Bogart, we primarily use covered calls as an income strategy for clients with large positions of concentrated stock. Let’s consider an example. (All of the examples in this section are purely hypothetical and ignore potential trading commissions and fees.)

Example Scenarios: Selling Covered Calls

Say you own 100 shares of stock currently trading at $90 a share and you sell a call option at $95 and collect a premium of $500. At expiration, the person who bought that contract has the right to buy your stock at $95 per share.

Scenario 1: The stock falls to $80 at expiration.

In this case, the contract would expire worthless. You keep your 100 shares of stock plus the $500 premium.

Scenario 2: The stock rises to $105 per share at expiration.

It’s likely the buyer will exercise his option to buy your shares, as he could earn $1,000 if he sold them immediately after. (The $10 difference between the market price and the strike price multiplied by 100 shares is $1,000.)

The other side of this equation means you would need to sell your 100 shares at $95/share. You earn a $500 profit from selling the stock at $95 instead of $90 ($5 x 100) and you keep the $500 premium; you’re up $1,000 from the time you sold the call option.

Covered Calls as a Diversification Strategy

In both scenarios, you-the investor selling the covered calls-end up in a better position than you were when you sold the call.

Not only are covered calls a great way to generate income, they can help with diversifying concentrated stock positions. If you own several hundred shares of company stock, covered calls can help you generate income as you sell those shares. Then, we can use the proceeds to buy other investments and build more diversity into your portfolio.

It’s important to make sure you’re comfortable selling 100 shares at the strike price before selling a covered call.

Using Put Options to Hedge

Most investors focus on long positions-that is, they buy investments and hope they increase in value. Options can create a bearish hedge-as in, hedge your bets-to help ease losses if those investments lose value. One common way to do this is by buying put options-the right to sell the underlying asset at a certain price on a certain date.

Say an investor owns many shares of a stock trading at $90; that investor might buy a put option that expires a year from now at a $70 strike price. If the stock falls to $65 in value in a year, the investor can buy 100 shares of the stock at $65 and then exercise the option at expiration to sell those shares above market price, at $70, making $500 in profit.

If the same stock increases in value to $100 by expiration, the investor would lose the money on the put contract and subtract it from any potential gains from the underlying stock.

With all options trading, you don’t need to keep the option until expiration. The prices of these contracts tend to change to reflect price changes in the underlying asset, meaning you can close the trade prior to expiration. You may also be able to roll the trade over to a later expiration, extending the timeline.

Risks and Complexity of Options Trading

Options tend to be risky because they’re leveraged-small changes in the underlying assets can result in big changes to the value of an options contract. Beyond that, the relationship between the price of an options contract and the price of an underlying asset is complex.

Both factors make options a much riskier investment than stocks, bonds, ETFs and mutual funds. That’s why we talk about options so infrequently when we discuss investing for the long term. However, you may still encounter options strategies inside funds or products you’re invested in, so it’s good to have a basic understanding.

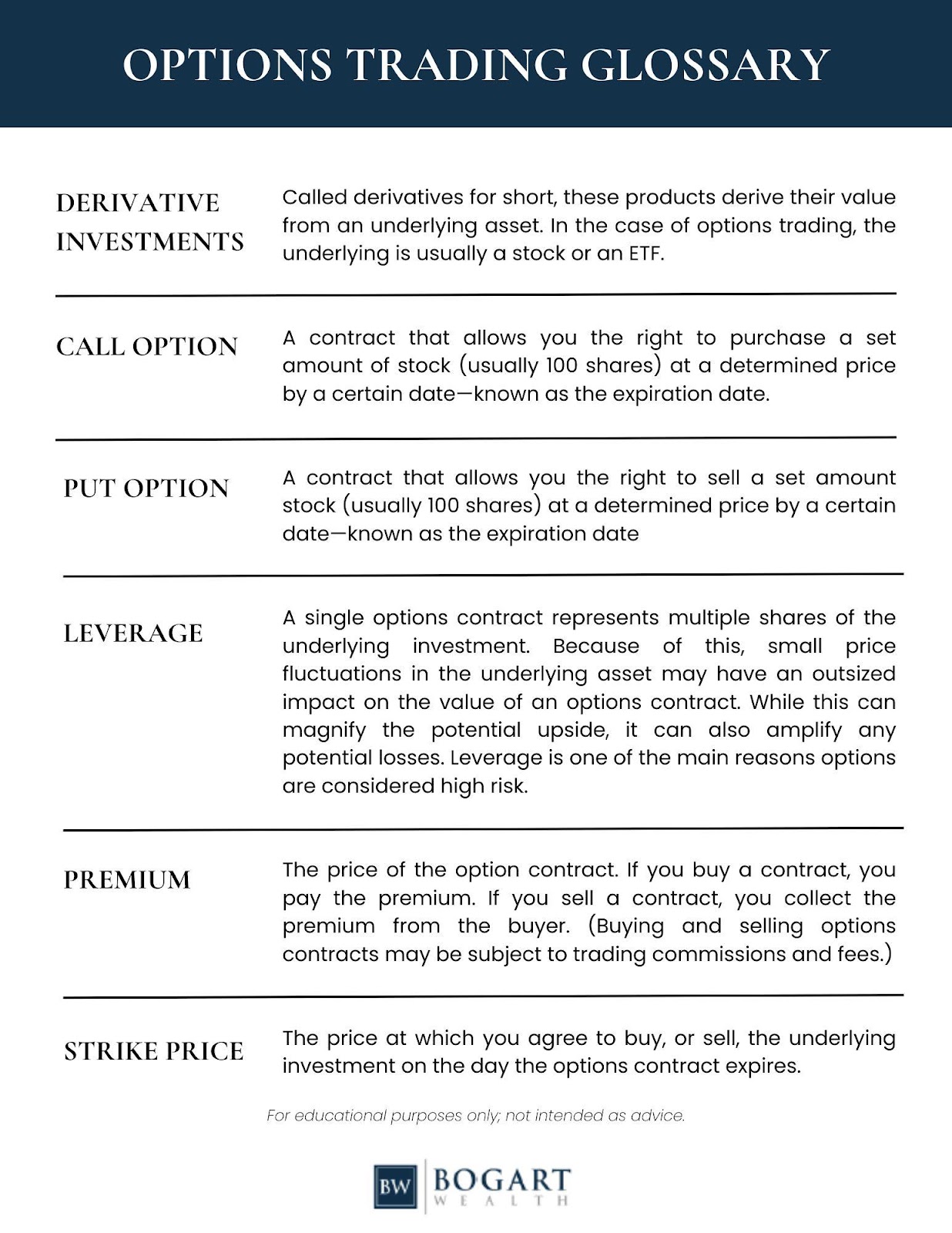

Want to learn how options, hedging, or income strategies could benefit your portfolio? Contact us today for personalized guidance. For quick reference, explore our glossary of key options terms below to boost your understanding.

Disclosures:

IMPORTANT DISCLOSURE INFORMATION

Covered call writing is the sale of in-, at-, or out-of-the-money call options against a long security position held in a client portfolio. This type of transaction is intended to generate income. It also serves to create partial downside protection in the event the security position declines in value. Income is received from the proceeds of the option sale. Such income may be reduced or lost to the extent it is determined to buy back the option position before its expiration. There can be no assurance that the security will not be called away by the option buyer, which will result in the client (option writer) to lose ownership in the security and incur potential unintended tax consequences. Covered call strategies are generally better suited for positions with lower price volatility.